The 12 best investments for the world

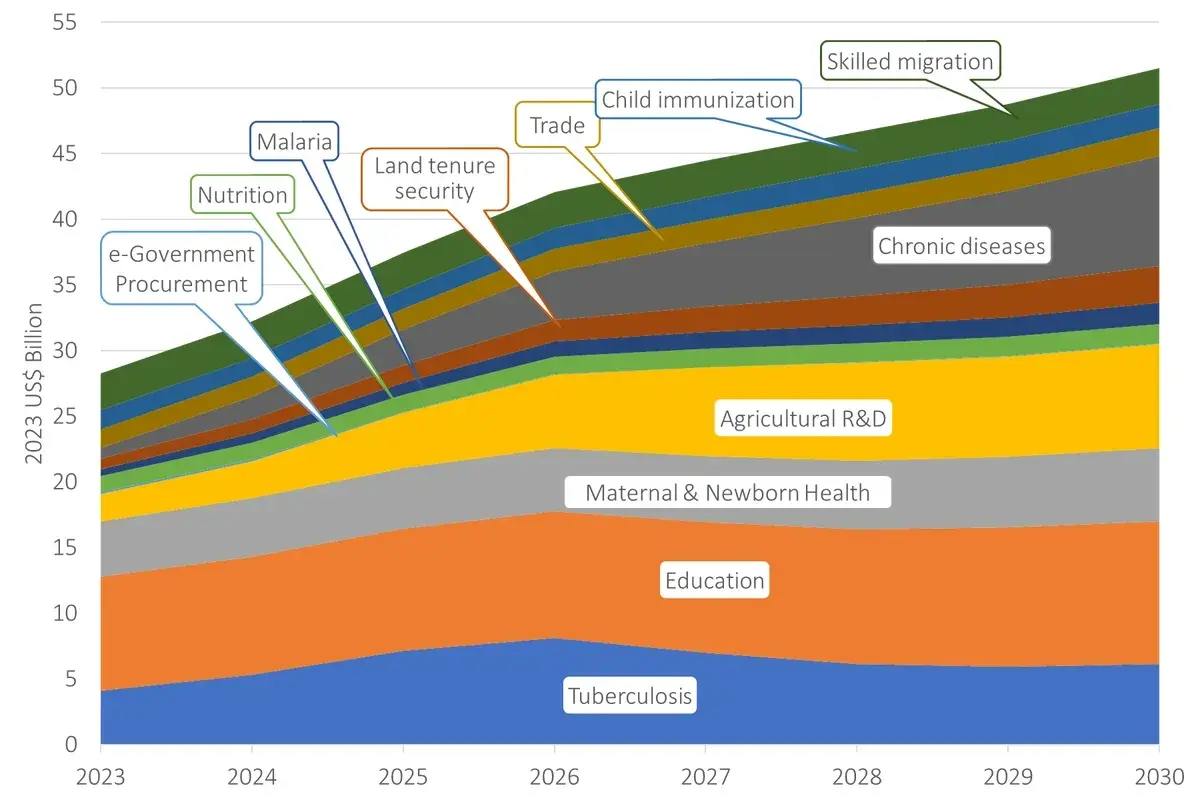

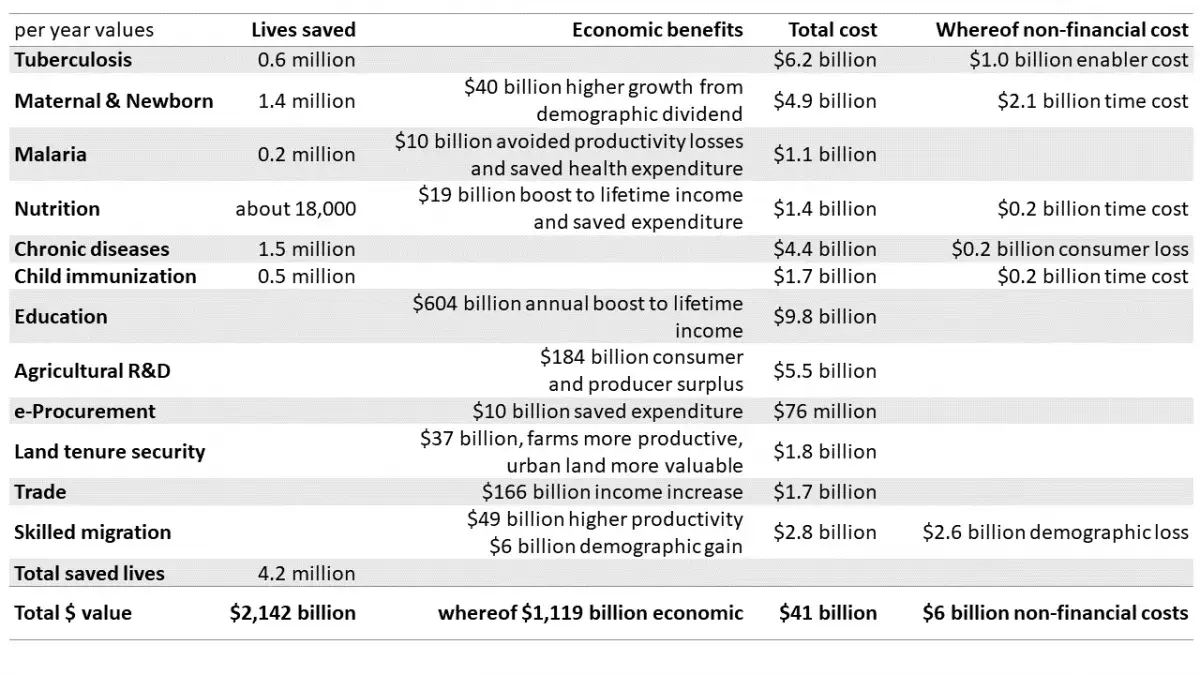

The 12 best policies, our experts have identified, cover a wide range of areas: tuberculosis, education, maternal and newborn health, agricultural research and development, malaria, e-procurement, nutrition, land tenure security, chronic diseases, trade, child immunization and skilled migration.

These have both costs and benefits. The annual costs, as shown in the figure below, rise from $30 billion to almost $50 billion by the end of the decade, for an average cost of $41 billion per year. The 2030 cutoff just denotes the end of the SDG era — these policies would also be phenomenally efficient in the years and decades after. Indeed, for some of them, the researchers estimated the costs and benefits far beyond 2030, as indicated in the individual analyses.

These have both costs and benefits. The annual costs, as shown in the graph above, rise from $30 billion to almost $50 billion by the end of the decade, for an average cost of $41 billion per year. The 2030 cutoff just denotes the end of the SDG era — these policies would also be phenomenally efficient in the years and decades after. Indeed, for some of them, the researchers estimated the costs and benefits far beyond 2030, as indicated in the individual chapters.

Some of these costs are non-financial, such as time costs for mothers to get their children vaccinated, or for tuberculosis patients to go to support meetings. These non-financial costs sum to about $6 billion annually, and they do not need to be financed by higher taxes or additional philanthropists’ checks. So, of the total cost of $41 billion per year, we will actually just have to marshal about $35 billion a year to pay for these policies.

The benefit of these 12 best policies can really only be described as momentous. It will save 4.2 million lives each year and generate $1.1 trillion in additional benefits each and every year (as you can see in the table below).

It’s easy to become inured to such huge numbers, so let’s pause a moment to reflect on how immense this really is. Saving 4.2 million lives in 2024 is equivalent to stopping one 747 jumbo jet full of passengers from crashing once an hour of every day for the entire year.

Then, saving 4.2 million lives in 2025 is equivalent to avoiding the eradication of the entire population of New Mexico and Nebraska. Saving 4.2 million lives in 2026 is like avoiding the death of the combined populations of Estonia, Eswatini, Djibouti and Guyana. And so on.

Across the decade, each year about 30 million people are expected to die in the poorer half of the world. These policies could avoid every seventh of those deaths. For every seven mortal tragedies that will play out over the rest of this decade, these policies could avoid one.

And that is just the effects up to the end of the decade. Most of the policies highlighted in this project will set us up for saving more lives far beyond 2030. Treatment for tuberculosis, for instance, will save 600,000 annually in this decade, but the resulting dramatic reduction in the disease’s spread will mean much lower death figures far into the coming decades.

The economic gains are also something to marvel at. Achieving $1.1 trillion in economic benefits split across the population of the poorer half of the world comes to $278 a person, annually. That is almost one additional dollar to every person every day. With low and lower-middle income countries clocking in at $10 trillion GDP in 2021, that means an 11% boost to their economies each year.

Notice that most of the economic benefits will only arrive in the future from better long-term economic performance. Take education policies that deliver about half the total $1.1 trillion annual benefits. The costs of $9.8 billion (almost all financial costs for teachers, classrooms, tablets and software) will make children across the poorer half of the world learn much more. When they become adults, they will be more productive, and the ones with a job will receive higher pay for many decades to come. The present-day value is $604 billion, as the value of these future income increases are discounted to today. The actual inflation-adjusted increases will be much higher, but most are many decades away.