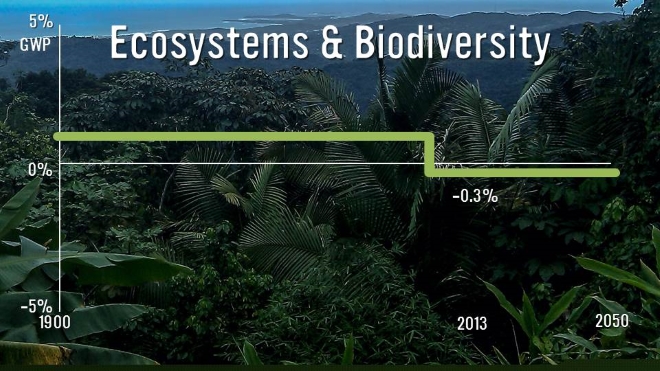

A Scorecard for Humanity: Ecosystems & Biodiversity

Assessment Paper

A version of the working paper is available for download here. The finalized paper has been published in How Much Have Global Problems Cost the World? A Scorecard from 1900 - 2050 by Cambridge University Press.

An Assessment Paper on ecosystems and biodiversity was written by Anil Markandya and Aline Chiabai and released as a chapter in How Much Have Global Problems Cost the World?

Much has been written and said on the loss of biodiversity that we have been experiencing in recent decades. Species are estimated to be going extinct at rates 100 to 1000 times faster than in geological times. Moreover there is reason to believe that these extinctions are associated with economic and social losses. For example, between 1981 and 2006, 47 percent of cancer drugs and 34 percent of all `small molecule new chemical entities´ (NCE) for all disease categories were natural products or derived directly from them. In some countries in Asia and Africa 80 percent of the population relies on traditional medicine (including herbal medicine) for primary health care. As extinctions continue the availability of some of these medicines may be reduced and new drug developments may well be curtailed. Yet, while we have a number of pieces of anecdotal evidence of this nature, and there are several studies that look at the value of biodiversity in specific contexts, no one has estimated the global value of the loss of biodiversity as such. This is because the links between biodiversity and biological systems and the economic and social values that they support are extremely complex. Even the measurement of biodiversity is problematic, with a multi-dimensional metric being regarded as appropriate but with further work being considered necessary to define the appropriate combination.

For this reason the focus, initiated by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), has been on measuring ecosystem services, which are derived from the complex biophysical systems. The MEA defines ecosystem services under four headings: provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting and under each there are a number of sub-categories.

The first thing to note is that services from ecosystems have also been facing major losses. During the last century the planet has lost 50 percent of its wetlands, 40 percent of its forests and 35 percent of its mangroves. Around 60 percent of global ecosystem services have been degraded in just 50 years.

While working at the ecosystem level makes things somewhat easier it is of critical importance to understand the causes of the loss of these services and the links between losses of biodiversity and the loss of ecosystem services. Indeed this is a major field of research for ecologists in which one thesis that has been developed over a long period is that more diverse ecosystems are more stable and less subject to malfunction. Evidence in support of this has been provided from a range of natural and synthesized ecosystems, but the evidence also point to more complex relationships, in particular to the fact that the functions of ecosystems are determined more by the functional characteristics of the component organisms rather than the number of species. Overall, however, many ecologists would agree with the statement that “diversity can be expected, on average, to give rise to ecosystem stability”, McCann, 2000, p.232.

To sum up, the current state of knowledge on the links between biodiversity and ecosystem services is still a topic of research and while some clear lines are emerging, they are not strong enough to allow a formal modelling to be carried out at a level that would produce credible estimates of the global value of biodiversity. The latter therefore remains a topic for research.