Malawi Priorities: Industrialization and Youth Employment

Technical Report

Key Messages

- Malawi’s youth have constrained opportunities for decent and full-time employment. A quarter of the youth in Malawi are underemployed, and almost all youth are employed in the two lowest skill tiers of employment, including youth who have finished secondary and tertiary education. More than 40% of youth who are deemed highly-skilled only work in jobs that require low skill levels, typically self-employed, informal, micro-enterprises that have limited value addition.

- The root cause of the youth underemployment and unemployment in Malawi is a lack of jobs which itself is caused by limited structural transformation of the economy. Internationally and in Malawi, the typical policy response to youth employment challenges is to focus on vocational and skills training for youth. However, this approach neglects the demand side of the labor market. Boosting industrialization and the broader business environment can stimulate firm growth that would naturally employ more skilled labor.

- Industrialization is defined more broadly than simply the growth of manufacturing services but rather as a process of economic transformation that results in employment creation. To that end, a number of tradable services industries share many characteristics as manufacturing, particularly the capacity to create better jobs. They benefit from productivity growth, scale, and agglomeration economies. This analysis focuses on two interventions in that sphere: A poultry out-grower model that strengthens market linkages to increase the value of agricultural commodities in Malawi and a credit guarantee scheme for medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs).

- The poultry out-grower model strengthens connections between small-scale poultry farmers, commercial poultry farms, and soybean processors. Small-scale poultry farmers can use soybean oilcake to generate more and higher-quality eggs for commercial poultry farms. At the same time, this would increase demand for soybean oilcake, utilizing existing capacity which is currently idle. The intervention would generate MWK 1.4 for every MWK 1 invested and 10,800 years of employment between 2021 and 2040. The benefits of agro-processing value chain integration can be expanded through exports.

- The Credit Guarantee Scheme (CGS) aims to provide MSMEs with greater access to formal finance, improving their ability to invest in production-enhancing inputs, including hired labor. The intervention generates MWK 1.05 for every MWK 1 invested and 11,776 years of employment between 2021 and 2026.

- International experience has shown there is no ‘silver bullet’ for industrialization and job growth in any economy. This paper demonstrates the potential for job creation from addressing barriers in market linkages and access to finance in two relatively narrow and specific areas. Mass employment requires a portfolio of targeted interventions. Besides these two interventions, other research papers in the Malawi Priorities series provide complementary interventions that support Malawi’s wealth and job creation aspirations including land titling, agricultural commodity exchange reform, energy sector reform, improving education quality, and artisanal and small-scale mining support.

Context

This analysis grew from two distinct research questions: “Where should Malawi focus its resources to achieve industrialization?” and “Which policies can effectively address youth unemployment and underemployment?” In considering the challenges and opportunities for both areas, the authors recognized a number of overlaps and common spaces for growth, and as such, the analysis was merged. Malawi’s young workforce participants are reliant on Malawi’s ability to improve industrialization, without which any amount of skilled labor would remain unused.

Since 1980, Malawi’s growth has fallen behind the Sub-Saharan Africa average, with weak and volatile growth highly dependent on rainfed agriculture and unreliable agricultural outputs. Maize and tobacco have been at the center of Malawi’s politics and economy, however, in order to achieve economic growth, there is a need for product diversification and investment in measures that promote productivity. At the same time, Malawi’s youth have constrained opportunities for decent and full-time employment. A quarter of the youth in Malawi are underemployed, and almost all youth are employed in the two lowest skill tiers of employment, including youth who have finished secondary and tertiary education. More than 40% of youth who are deemed highly-skilled only work in jobs that require low skill levels, typically self-employed, informal, micro-enterprises that have limited value addition. Conventional skill development programs, which are regularly conducted in response to youth unemployment, fail to adequately respond to these challenges

Intervention 1: Poultry Farm Outgrower Scheme

Malawi’s agro-processing value chains are characterized by weak linkages and inefficient marketing channels, largely driven by infrastructure gaps and information asymmetries between stakeholders. There is often a mismatch between supply and demand for agricultural products, and it can be challenging for agro-processors to achieve profitable margins. The animal feed to poultry sector value chain is one such example of a value chain that could benefit from greater integration. The intervention modeled in this study is a poultry farm out-grower scheme that aims to strengthen connections between small-scale poultry farmers, commercial poultry farms, and soybean processors. Small-scale poultry farmers can use soybean oilcake to generate more and higher-quality eggs for commercial poultry farms. At the same time, this would increase demand for soybean oilcake, utilizing existing capacity which is currently idle.

Figure 1: Key barriers to employment growth

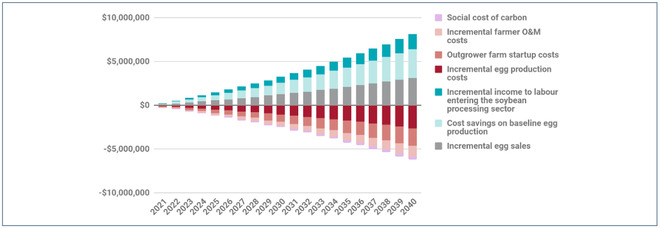

Costs and Benefits

The primary benefits of this intervention are the increase in egg sales, cost savings through increased efficiency of egg production, as well as the increased income to labor entering the soybean processing sector. Costs include start-up capital costs, recurring capital and operations, and maintenance costs, and the social cost of carbon emissions.

The intervention would generate MWK 159 million initially, rising to MWK 6,050 million by 2040. 80% of the benefits accrue to the poultry sector in terms of higher egg sales and cheaper production costs, with the rest going to the soybean sector. The cost of the intervention is MWK 222 million rising to MWK 4,337 million for startup and ongoing costs for out-grower farmers. The intervention would generate MWK 1.4 for every MWK 1 invested and 10,800 years of employment between 2021 and 2040. The benefits of agro-processing value chain integration can be expanded through exports. The results of the poultry egg outgrower scheme modeled in this study are based on projected domestic demand for poultry eggs. The Government of Malawi could work with entities such as the Malawi Investment and Trade Commission to identify opportunities to expand exports of poultry eggs to regional neighbors to expand and diversify the benefits of value chain integration.

Intervention 2: Credit Guarantee Scheme

Formal lenders cannot easily distinguish between good and bad borrowers. As such, formal loans are set at higher rates, forcing many SMEs out of the formal financial market. These credit-constrained SMEs may be unable to invest in production-enhancing inputs, including hired labor. On the other hand, financiers are often unable or unwilling to lend to SMEs due to the relatively high risk of default compared to larger firms. To help address these issues, the intervention model is a credit guarantee scheme to provide SMEs with greater access to formal finance. However, it is important to note that the government should not engage in loan generation in the space of banks. Banks have the infrastructure, incentives, and capability to assess lending risk. Instead, the role of the government should be to assume some of the risks of lending, that the banks would not otherwise.

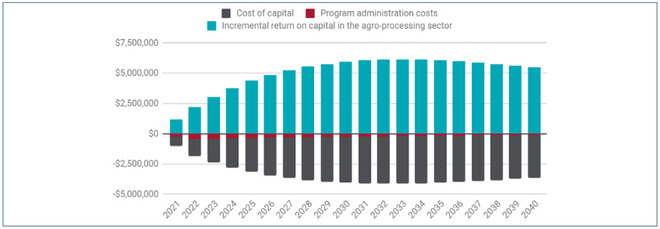

Costs and Benefits

The primary benefits of this intervention are the increased return on capital to SMEs who gain access to credit through the intervention, as well as the SME surplus that accumulates from a reduction in the cost of borrowing. By 2026, the intervention would require MWK 10,712 million in costs of financing, defaults and administration but generate MWK 11,039 million in returns and surplus for MSMEs. The intervention generates MWK 1.05 for every MWK 1 invested and 11,776 years of employment between 2021 and 2026.

Overall Policy Implications

The root cause of the youth underemployment and unemployment challenge in Malawi is a lack of jobs which itself is caused by limited structural transformation of the economy. While many youth employment programs cite a lack of skills as a constraining issue, skills development alone will not address the challenge of youth employment in Malawi.

Demand-driven education and skills development programs are still needed. Due to the mismatch of demand and supply in the labor market in Malawi, it is likely that economic growth will need to be accompanied by investment in education and infrastructure to connect youth to employers. These programs should be designed and funded based on the skills demanded by the job market.

Industrialization is defined more broadly than simply the growth of manufacturing services but rather as a process of economic transformation that results in employment creation. To that end, a number of tradable services industries share many characteristics as manufacturing, particularly the capacity to create better jobs. They benefit from productivity growth, scale, and agglomeration economies.

Any intervention that might be designed should undertake a thorough assessment of considerations related to land tenure. Land tenure is an exceedingly complex and often contentious matter which should be a central consideration of any intervention that is designed to advance industrialization and youth employment in Malawi. Poorly designed interventions can cause more harm than good by excluding marginalized citizens from accessing benefits or, worse yet, further marginalizing people by dispossessing them of their livelihoods.

International experience has shown there is no ‘silver bullet’ for industrialization and job growth in any economy. Mass employment requires a portfolio of targeted interventions: While the interventions modeled in this study are expected to yield net benefits for Malawi’s economy, they fall well short of the 1 million jobs that the Government of Malawi hopes to create during its term. This level of job creation will require a larger portfolio of interventions, of which the two we have modeled can serve as examples. Other research papers in the Malawi Priorities series provide complementary interventions that support Malawi’s wealth and job creation aspirations including land titling, agricultural commodity exchange reform, energy sector reform, improving education quality, and artisanal and small-scale mining support.

Figure 2: Costs and Benefits of Poultry Outgrower Scheme

Figure 3: Costs and Benefits of MSME CGS intervention

Summary Table

| Intervention | BCR | Costs | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Guarantee Scheme | 1.05 Fair | Costs over 6 years Capital costs (MWK 48,085 million) Program administration costs (MWK 3,348 million) |

Benefits over 6 years Increased revenue and surplus earned by MSMEs (MWK 54,100 million) |

| Poultry Outgrower Scheme | 1.3 Fair | Costs over 20 years Incremental egg production costs (MWK 17,790 million); Outgrower farm startup costs (MWK 14,369 million); Incremental farmer O&M costs (MWK 8,188 million) |

Benefits over 20 years Value added by poultry outgrowers(MWK 21,429 million) Cost savings on baseline egg production (MWK 22,355 million) Increased income to labor in soybean sector (MWK 11,778 million) |

Note: BCRs are based on costs and benefits discounted at 8% (see accompanying technical report). BCR ratings are determined on the following scale Excellent, BCR > 15; Good, BCR 5-15; Fair, BCR 1-5; Poor, BCR < 1. This traffic light scale was developed by an Eminent Panel including several Nobel Laureate economists for a previous Copenhagen Consensus project that assessed the Sustainable Development Goals.

Download the full policy brief here.