Ghana Priorities: Health Access

Technical Report

The Problem

The health status of Ghanaians has evolved over time, from predominant inflictions from infectious diseases and negative maternal and child health outcomes that prevailed at the time of independence in the late 1950s, to the addition of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, stroke, diabetes, cancers, etc. that prevail in present times. Indeed, according to the IHME (2017), stroke was one of the top ten causes of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in the country.

Disease patterns in Ghana often differ across age, gender, location and socioeconomic status. Malaria, for example, has led to high mortality among children less than 5 years of age. Maternal health problems have also been more dominant among poorer, rural women and those resident in the northern regions of the country. Although maternal and child mortality rates have decreased over time (e.g. in 1990 the maternal mortality ratio was 600 per 100,000 live births, in 2017, 310 per 100,000 (2017 Ghana Maternal Health Survey); in 1990 the child mortality rate was 128.2 per 1000 live births, in 2017, 55.6 deaths per 1,000 live births), the current rates remain higher than other countries with similar socio-economic backgrounds (MoH, 2015). Other diseases like trachoma, onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis (LF), schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthes are also particularly dominant among poor communities in Ghana, with a higher incidence observed among women (Allotey and Gyapong, 2005). Non-communicable diseases (NCD) tend to be more prominent among adults in their reproductive ages; diabetes is more prominent among men in the country while obesity is more pronounced among women (Agyemang et al., 2016).

This co-existence of infectious and non-communicable diseases with differential prevalence and impacts among individuals of varying social classes has implications for health care delivery and indeed, the double burden of infectious and NCDs present a challenge for the current health care system. There is a general consensus in Ghana, and in many other developing country contexts, that majority of health problems observed are experienced by the poor (Bukhman et al., 2015). First, poor households experience the most catastrophic healthcare expenditures (Surhcke et al., 2006); Second, the poor live in less safe and sanitary environments with increased likelihoods of disease infestations; Third, the poor have limited social support systems (de-Graft Aikins and Koram, 2017); Fourth, the poor lack participatory power in changing community and health systems (Greif et al., 2011; Capewell and Graham, 2010).

The situation has contributed to political and policy responses in an attempt to deal with both changing dynamics of health and its differential impacts. This paper discusses a range of interventions that are aimed at improving Ghana’s health sector through the analyses of their corresponding costs and benefits. The results presented will help to provide evidence-based rationale for investments in high-priority areas that are likely to improve both health care and welfare outcomes within the country.

Intervention 1: Improve targeting of NHIS premiums to ensure richer individuals pay higher premiums and abolish user fees and annual premium payments in deprived communities

Overview

The establishment of a health insurance scheme was borne out of the desire to abolish the ‘cash and carry’ system that characterized the health system where patients were required to make initial payments before receiving health care services. Before the advent of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), many Ghanaians were unable to access quality health care services as a result of high user fees (Nyonator and Kutzin, 1999; Asenso-Okyere et al., 1998; Hutchful, 2002). The NHIS was introduced to address the inequality in health care access by reducing out-of-pocket payments, particularly among the poor. Recent assessments of the scheme however indicate that poor households are not adequately covered under the scheme despite heavily subsidized premiums (Aryeetey et al., 2011; Kotoh and Van der Geest, 2016). The abolishment of user fees and annual premium payments in deprived communities and among poor households may be expected to affect both the demand for health care and subsequently, health outcomes among this segment of the population.

Standard economic theory posits that health insurance coverage induces greater medical care use by reducing the cost of care to patients . Insurance may also influence the quality of health services through provider accreditation processes, modes of provider payment, and, more generally, by ensuring consistent flows of funding to providers. All other things being equal, therefore, those affected by the removal of health insurance premiums should experience fewer financial barriers to access and therefore use more health care. We further speculate that health status is likely to improve as a result of increased access to health care.

Implementation Considerations

Currently 23% of the country is classified as poor or approximately 7 million people. Of these some 2.7 million people do not have health insurance. The intervention calls for a registration drive to insure the remaining poor, plus the transfer of registration payments of GH¢30 and premium fees of GH¢6 from the 23% of Ghana’s population that is poor to the non-poor segment of the population. The costs of the intervention include the initial registration drive, increased premium payment by the rich, in addition to increased expenditure by the National Health insurance Authority (NHIA) as a result of the presumed increased health demand by the poor. Benefits of the intervention include declines in all-cause mortality, in addition to a decline in morbidity.

Costs and Benefits

We use data from a number of different sources in computing the corresponding costs and benefits of this intervention, including claims expenditures from the National Health insurance Authority and mortality and health data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

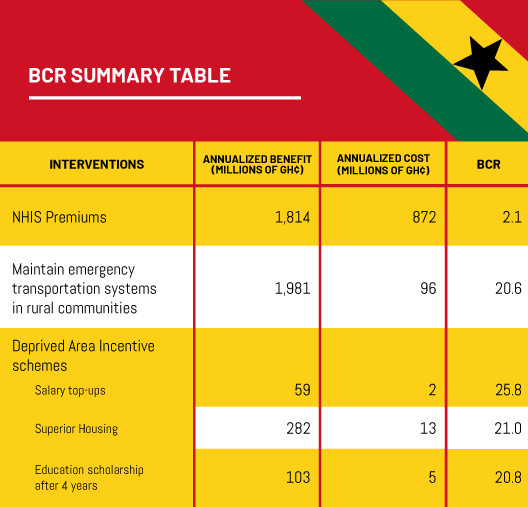

In the first year, it is assumed that a registration drive to find and enroll the remaining poor will cost GH¢ 27m. After this, the costs of the intervention include the transfer of premiums of GH¢ 212m plus increased health expenditures of the newly enrolled of GH¢ 603m per year. The total cost of the intervention over 10 years is estimated at GH¢ 5.8bn or an equivalent annualized cost of 872m per year. Increased health expenditures by the newly enrolled dominate the cost profile.

The intervention is expected to avoid 1,728 deaths as well as a staggering 25,500 years lost to disability annually. The total benefits of the intervention over a 10 year period are estimated at GH¢ 12.1bn or an annualized value of GH¢ 1.8bn.

Intervention 2: Maintain ambulance and emergency transportation systems in rural communities

Overview

Access to formal health care is a critical characteristic of an efficient and well-integrated health care delivery system. In most developing countries, however, there may be interruptions that hamper access to such care. These interruptions, according to Thaddaeus and Maine (1994) may be due to delays in the decision to seek formal care, delays in reaching the health facility or delays in receiving appropriate treatment at the health facility. Overcoming the second delay of reaching health centres is particularly challenging for the rural population due to the long distance to health facilities and the absence of efficient public transportation in these difficult to reach terrain in remote communities (Sulemana and Dinye, 2014). Moreover, Thind et al. (2015) highlight the potential of such prehospital emergency transportation in addressing the burden of diseases particularly for maternal and child health conditions, as well as trauma and injuries given their high prevalence in such rural communities.

To address this challenge, other developing countries in sub-Sahara Africa have intervened with the use of terrain suitable emergency transportation systems in rural communities, which have yielded positive results, according to the systematic review conducted by Hussein et al. (2012). Evidence from such interventions suggests that improving access to formal health care provides significant benefits with regards to reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. Also, fatalities associated with injuries and acute diseases show significant reductions from such interventions.

Implementation Considerations

The recent distribution of the ambulances to every constituency in the country makes the current analysis timely. Given that the ambulances have already been purchased, the analysis focuses on their maintenance to ensure an effective delivery of health care, particularly to the rural population which is the focus of the analysis. As at 2019, the rural population is estimated at about 44.5 percent of the Ghanaian population.

In this analysis, we consider costs associated with the operation of the ambulance system, including fuel, maintenance and repairs. Also, the analysis considers costs related to the training and remuneration of drivers and paramedics who play a central role in the emergency transport system. To ensure an efficient running of the emergency transport system, the study considers cost associated with the establishment of ambulance stations. These stations serve a dual purpose of being the central holding points of ambulances when they are not in use and for routine maintenance.

Besides these costs which are directly associated with the provision of the emergency transport system, it also anticipated that improved access to health facilities will increase demand for health care and, therefore, health care costs.

Concerning the benefits, we consider reductions in maternal, neonatal mortality and deaths from trauma and injuries based on information provided in studies from Ghana and abroad.

Costs and Benefits

In the first year, the cost of the intervention is GH¢ 385m, of which GH¢ 338m are for the ambulance houses. Thereafter, the annual cost of the intervention is GH¢ 46.5m for continued maintenance and operations, as well as increased health care expenditure. Based on this, the total cost projection for this intervention for the entire rural population in Ghana over 10 years is GH¢ 646 m, or an annualized cost of GH¢ 96m.

The intervention is expected to avoide 1,918 deaths per year due to improved and faster transfer of birthing mothers and trauma victims to health care facilities. The total benefits from the intervention are valued at GH¢ 13,297m across the 10-year projection, for an annualized benefit of GH¢ 1,981 million.

Intervention 3: Implement incentives schemes (such as the Deprived Area Incentive Allowance) to encourage more health services in poor and hard to reach areas.

Overview

Adequate delivery of health care would be difficult without an adequate health workforce. The population density of health care providers in a country directly impacts the provision of health services such as immunization and skilled birth attendance (Anand and Barnighausen, 2004; WHO 2006), and leads to a reverse correlation between health worker density and health outcomes such as infant mortality, maternal mortality and various disease-specific outcomes (Khann et al. 2003). In Ghana, the distribution of health workers is skewed in favor of the more affluent regions, most of which are found in the southern half of the country. In rural areas, the quality of health care delivery is compromised by low staff competencies, poor life-saving skills, poor record keeping, among others (MoH, 2011). There are also rural/urban variations in the coverage of skilled birth attendance: while it is 82% in urban Ghana, it is only 43% in rural Ghana.

Given that close to 50% of Ghana’s population resides in rural areas, ensuring access to health care services in these parts of the country is essential to achieving national goals of universal health coverage and equity in the distribution of care. In Ghana and in many other parts of the developing world, health policymakers and managers are searching for ways to improve the recruitment and retention of staff in remote and deprived areas. The intervention described here assesses the cost-effectiveness of providing various incentives to attract and retain health workers in deprived and rural areas of Ghana.

Implementation Considerations

The intervention seeks to encourage doctors to work in the rural areas of the three northern regions of Ghana where 2.3 million Ghanaians live. Incentives considered include salary top-ups, housing allowances and education scholarships. The analysis assumes that currently the doctor to patient ratio in these areas is 20,000. In other words, there are currently only 116 doctors serving these communities.

Costs and Benefits

The various incentives have different costs and effects. Increasing the base salary by 30% is expected to cost GH¢ 2.3m per year and incentivize 44 more doctors to work in these areas. Providing superior housing is expected to cost GH¢ 13.4m per year and incentivize 207 more doctors to work in the rural north. Lastly, an incentive that provides an education scholarship for four years service, is expected to cost GH¢ 5.0m per year and incentivize 76 more doctors to work in the remote north.

Each new doctor in these regions is assumed to avoid 0.27 and 1.45 maternal and infant deaths respectively (Saluja et al., 2020) within the target population per year. Therefore increasing the base salary by 30% would lead to 75 deaths avoided, providing superior housing would also lead to 357 deaths avoided and an education scholarship, 131 deaths avoided. The benefits are valued at GH¢59m, GH¢282m and GH¢103m respectively. Corresponding BCRs are therefore 25.8, 21.0 and 20.8 for these incentives.