Malawi Priorities: Water Reliability

Technical Report

Key Messages

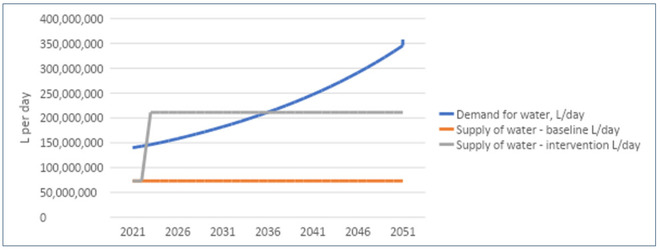

- Blantyre has insufficient water to meet demand. The average daily demand of 140 million liters per day vastly outpaces the Blantyre Water Board’s (BWB) maximum supply of 122 million liters per day. Taking into account 40% water losses prior to consumption, the shortfall between water supply and demand is more than 70 million liters per day. While there is a high level of access to formal water service, this shortfall contributes to unreliable and intermittent service provision. Unreliable water leads consumers to engage in costly coping strategies such as installing boreholes, storing water in buckets and reservoirs, traveling to the next nearest source, or in the case of industry and business, loss of output.

- The primary recommendation of the paper is to pursue a combination of two interventions: The development of a new water source from the Shire River and a rollout of the E-Madzi program (automated water kiosks) to Blantyre. The combined intervention yields 3.2 kwacha for every kwacha invested, higher than either intervention alone. However, the analysis shows that the BWB should wait until the new supply is fully implemented and that a sufficient proportion goes to informal settlements, before considering any rollout of E-Madzis. The benefits of the e-Madzis investment are greater the more water that is supplied to kiosks, reducing wastage, water operating costs, and waiting time.

- The paper confirms the economic rationale for pursuing the Blantyre Water Board’s proposed development of a new water source from the Shire River, which will increase Blantyre’s water supply by approximately 230 million liters per day sufficient to meet the city’s needs until 2036. The intervention is costed at MWK 122,925 million in upfront investment and recurrent costs of MWK 17,865 million rising to MWK 33,708 million. The benefits of the new water supply would be substantial, equivalent to 0.6% of Malawi’s GDP. Overall, for every kwacha invested, this intervention alone would yield 2.8 kwacha in benefits and rises to 3.2 if implemented along with E-Madzis.

Context

Despite the recent completion of the Likhubula water supply project, Blantyre is plagued by water shortages. The new infrastructure increased the Blantyre Water Board’s (BWB’s) capacity to 122 million L of water daily. However, this is still less than the estimated average demand of 140 million L per day. Additionally, large physical water losses mean that 40% of the water supply is lost before it reaches the consumer, exacerbating the shortfall. As a result, water is not available 24 hours per day, and most residents (85%) utilize a secondary source of water when their main source of water is unavailable. On average, public taps, boreholes, and protected springs were only available for 12 h per day, due to limited opening hours and irregular supply, while drinking water from a private tap is available for 21 h per day.

Unreliable water imposes costs on water users. Consumers store water in their homes or are forced to travel to other water sources to meet their needs. Across Malawi, around 16% of urban dwellers get their water from boreholes which are typically outside of the main water board’s supply system, a phenomenon confirmed by the Blantyre Water Board. All of these coping strategies require extra costs, extra time, or both. The largest burden of insufficient supply falls upon Blantyre residents living in informal settlements, who are mostly serviced from the city’s water kiosks. Despite the fact residents in informal settlements makeup around 60% of inhabitants in Blantyre, kiosks only provide 4% of supplied water.

In addition to these challenges, the BWB further struggles with revenue collection, inefficiencies in administration, indebtedness, and the unaffordability of water.

Intervention Component 1: Development of a new water source from the Shire River

Irregular water supply emerges as the BWB’s biggest problem. With the supply of water evidently falling short of demand, the BWB has plans to invest in a new water source from the Shire River. The plans include a water treatment plant, pumping stations, water tanks, and pipelines to produce 230 million liters per day in 2023. This intervention is expected to directly address the interruptions in service owing to inadequate supply and is one of the future projects identified by the Blantyre Water Board. However, the intervention is currently only 47% financed with a loan from India’s Exim Bank (BWB, 2021).

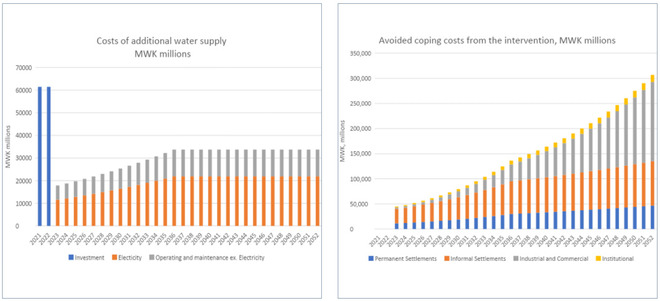

For an upfront investment of MWK 122,925 million and recurrent costs of MWK 17,865 million rising to MWK 33,708 million, the new supply of 230 million L per day would likely be sufficient to meet demand in Blantyre until 2036, even after accounting for 40% physical losses.

The primary beneficiaries of the intervention would be residential consumers – both those living in informal and permanent housing areas, who make up the largest portion of the present demand gap. Industrial, institutional and commercial customers would also have their water demands met. Benefits are primarily expressed in avoided coping costs which residential, institutional, and commercial customers would otherwise have to incur. The intervention would generate benefits worth MWK 44,770 million in 2023, the assumed the first year of operations, rising to MWK 306,887 million by 2052.

Being the commercial center of Malawi, ensuring Blantyre has sufficient water is essential for both the city and the country’s economic growth. As such, the benefits of this intervention alone are equivalent to 0.6% of the projected GDP. The return-on-investment from the intervention by itself is 2.8, meaning that for every kwacha spent on the project, Blantyre receives 2.8 kwacha in economic benefits, and rises to 3.2 if combined with the E-Madzi intervention.

Figure 1: Demand, Supply of water per day with and without intervention

Figure 2

Intervention Component 2: Roll-out of e-Madzi kiosks across Blantyre

The second intervention is the installation of E-Madzi kiosks across Blantyre, based on a pilot rolled out in Lilongwe. These E-Madzi kiosks are automated water dispensers that replace in-person kiosks while ensuring increased access to water and lowering water costs by 65%. With residents in informal settlements unable to pay for connection fees and water authorities unwilling to extend the piped network to environmentally sensitive areas, the water kiosks are considered critical to providing and maintaining water supply to low-income areas and are managed by the WUA.

The intervention proposed is to replace traditional (manual) water kiosks with e-Madzi kiosks across all 730 functional kiosks in Blantyre. The E-Madzi kiosks respond directly to the problems of NRW, inconsistent access, and unaffordability. Residents can also access water at any time, as the traditional kiosks were only open for a portion of the day when they can be staffed. Finally, the technology helps to reduce water wastage due to spillage and non-revenue water because the release of water is automated, accessible through a smart card. The costs of the intervention are MWK 3,357 million for the installation of the automated kiosks, program management, and the purchase of smart cards. Maintenance is estimated at MWK 163 million per year. Replacement of smart cards occurs every 5 years, while E-Madzis are

The benefits of the intervention are a reduction in water costs by 65% and a reduction in waiting time by 5 min per trip. There is also a reduction in congestion which reduces the spread of infectious disease, notably COVID-19, though this benefit was not quantified in the analysis.

The benefits are highly dependent on the amount of water that is supplied to the kiosks. If the new water supply intervention is not implemented, and the kiosks continue receiving only 4% of water, the benefits are only 1.5 times the costs of the E-Madzis. However, if the E-Madzis are rolled out after the water supply project is installed, then the benefits jump substantially and the return on investment for the combined intervention is 3.2.

Intervention Component 3: An intervention with both increased water supply and E-Madzis has a higher return on investment than either intervention alone

While alone, these interventions generated positive returns on investment, in a scenario where both interventions are implemented simultaneously, the incremental BCR of both interventions jumps to 3.2, meaning that every kwacha invested yields 3.2 kwacha in benefits, indicating that the two interventions are synergistic. This is based on a thirty-year water supply project and E-madzis installed in 2022 and replaced in 2032 and 2042.

Summary Table

| Intervention | BCR | Costs MWK, millions | Benefits MWK, millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Source Development from the Shire River & E-Madzi Rollout to Blantyre (together) | 3.2 Fair (100% economic benefits) |

Sum of cost figures below | Reduced coping costs from unreliable water: MWK 44,770 million in 2023, rising to MWK 306,887 million by 2052 Reduced costs of kiosk water: MWK 8,000 million every year Time savings from reduced queuing: MWK 12,630 million initially rising with income growth |

| New Water Source Development from the Shire River (alone) | 2.8 Fair (100% economic benefits) |

Upfront cost: MWK 122,925 million in upfront investment Operating and electricity cost: MWK 17,865 million in 2023 rising to MWK 33,708 million in 2052 |

Reduced coping costs from unreliable water: MWK 44,770 million in 2023, rising to MWK 306,887 million by 2052 |

| E-Madzi Rollout (alone) | 1.5 Fair (100% economic benefits) |

E-madzis: MWK 3,290 million replaced every 10 years Smart cards: MWK 67 million replaced every 5 years Maintenance: MWK 163 million every year |

Reduced costs of kiosk water: MWK 521 million every year Time savings from reduced queuing: MWK 418 million initially rising with income growth |

Note: BCRs are based on costs and benefits discounted at 8% (see accompanying technical report). BCR ratings are determined on the following scale Excellent, BCR > 15; Good, BCR 5-15; Fair, BCR 1-5; Poor, BCR < 1. This traffic light scale was developed by an Eminent Panel including several Nobel Laureate economists for a previous Copenhagen Consensus project that assessed the Sustainable Development Goals.

Download the full policy brief here.