Malawi Priorities: Nutrition

Technical Report

Key Messages

- Using cost-benefit analysis to determine which interventions provide the strongest impact for additional funds, this report finds that two key interventions show promise and represent good uses of funds to tackle the challenge of undernutrition in Malawi. These are:

- Breastfeeding promotion, to encourage mothers to breastfeed their babies exclusively from birth to five months old and to continue after weaning up to 23 months old. This program would increase exclusive breastfeeding by 21.6 percentage points, averting 334 child deaths in the first year, and a total of 2,088 deaths over a six-year period. Scaling up breastfeeding promotion through the recommended intervention would incur a cost of MWK 5,504 million over a five-year period. Overall, this intervention yields a benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 5.4, meaning that 1 kwacha invested yields 5.4 kwacha in social and economic benefits.

- Complementary Feeding Promotion (CFP) would inform mothers of the benefits of age-appropriate feeding post-weaning, ideally in combination with continued breastfeeding. Of the two interventions, this intervention exhibits a higher BCR at 7.2, and would avert stunting in 3,119 children in the first year, and 19,500 children over the full five-year program. CFP would require an investment of MWK 3,513 million over a five-year period.

- Other interventions considered, including flour fortification, cash transfers, nutrition sensitive agriculture and improved water and sanitation facilities were screened out because of low BCRs from previous studies, lack of data, or because they were not prioritized by sector experts. Micronutrient supplementation which yields a BCR of 14, has been evaluated in a separate research paper on Maternal and Neonatal Health within the Malawi Priorities Project.

Context

Undernutrition and stunting present a number of challenges for children in Malawi. The long-lasting harmful consequences include diminished mental ability and learning capacity, poor school performance in childhood, reduced earnings, and increased risks related to diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Stunting cannot be corrected by treatment but has to be addressed through a multi-sectoral approach via interventions that promote healthy growth in the young child especially in the early years of life

Rates of stunting, although declining, remain at 37%. This is a greater problem in the countryside than in towns: rural children have a 39% likelihood of being stunted, compared to 25% for urban children. However, the entire country has high rates. This is not a regional issue. Since education and wealth are both inversely related to stunting (DHS 2015-16), reducing its incidence has longer-term benefits for the country’s future productivity in addition to the obvious gains in quality of life for individuals. According to the Cost of Hunger 2012 report, it is estimated that Malawi lost US $597 million due to undernutrition which is equivalent to 10.3% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

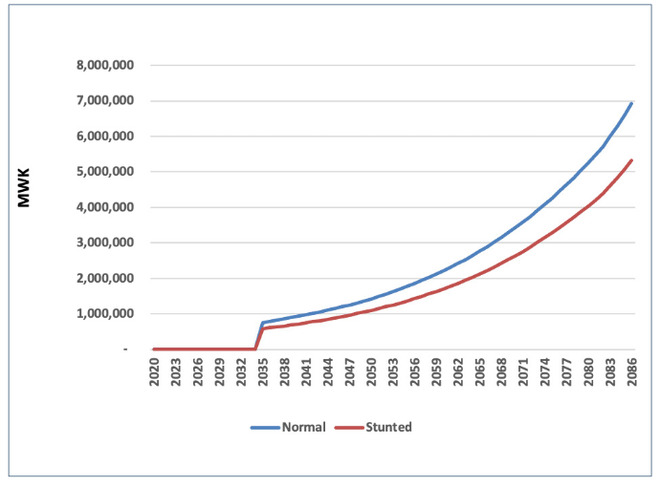

Figure 1: Average Income Divergence over a Lifetime for children born in 2020

Chronic undernutrition is the primary cause of stunting, but behind this lies a major problem of food insecurity. Low household incomes and low agricultural productivity are the main reasons for the lack of a secure and adequate food supply that affects 39% of households, or an average of 9.4 million people within the country. However, the underlying cause of child morbidity and mortality is multifaceted, not solely associated with poverty or food insecurity. In Malawi, 46 percent of children under five years are stunted among the poorest community compared to 24 percent among the wealthiest community (DHS, 2016) Early complementary feeding of babies is also common practice (only 61% of babies are exclusively breastfed up to six months of age according to the latest survey). Beyond that, just 8% of children receive a minimum acceptable diet between six and 23 months of age (DHS 2015-16).

At present, nutrition services are delivered through different service delivery platforms including at the facility level through growth monitoring promotion, antenatal clinics, outreach clinics, and IMCI. At the community level, nutrition services are provided through care groups and frontline workers from Health, Agriculture, Community Development, and Volunteers. Frontline workers include Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs), Agriculture Extension Development Officers (AEDO), Community Development Assistants (CDAs), and teachers. Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) who work directly with women and children in the community.

The system faces chronic resource constraints and problems with the quality of delivery. In light of these challenges, in 2017 Malawi launched the first National Community Health Strategy (2017-2022) in which the government committed to improving basic community health services throughout the country in collaboration with non-governmental organizations. Having a properly resourced, fully functional system across the country is obviously a prerequisite for the achievement of these strategic goals. In this context, it is particularly important to identify how to expand and improve the delivery of improved nutrition in a cost-effective way.

Summary of findings

Breastfeeding promotion

Exclusive breastfeeding of 0-5-month-old babies has been increasing in recent years, however, the past decade has seen this growth slow significantly, with prevalence rates plateauing and, in some cases, decreasing.

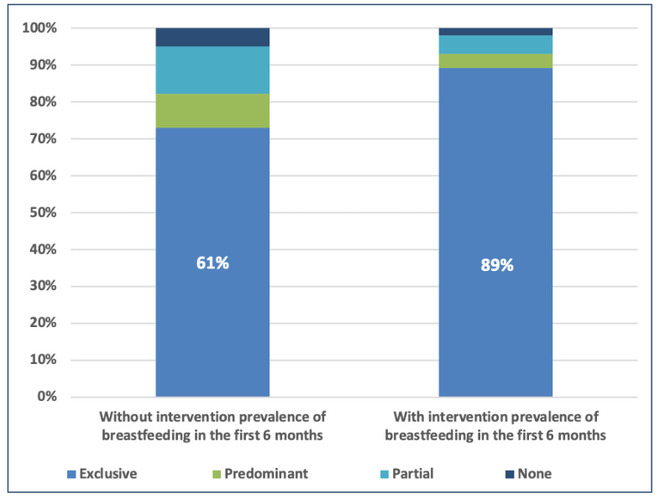

Figure 2: Promotion would increase exclusive breastfeeding by 21.6%

Increasing the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of a child’s life, as well as improving the prevalence of continued breastfeeding after weaning, and up to 23 months of age, reduces the risk of infection and associated morbidity and mortality of the child. In the longer term, improved cognitive development and reduced risk of non-communicable diseases (for both mother and child) help to increase human capital.

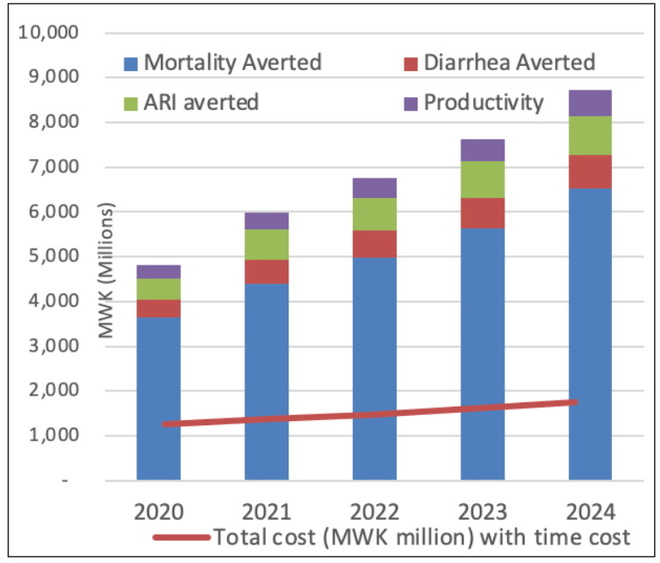

Bearing this in mind, the proposed intervention involves the promotion of breastfeeding via HSAs. The target population is 100,000 mothers in the first year, rising to 150,000 in the fifth and final years (this applies to both interventions). This would increase exclusive breastfeeding rates by 21.6 percentage points. Much of the cost of delivery is due to the provision and training, of staff, supplemented by the time taken for the promotion itself, which is to be six 30-minute consultations. Finally, there is a cost associated with the time commitment of mothers needed for exclusive breastfeeding. The total cost of the intervention is MWK 5,504 million over five years, starting at just over MWK 1,000 million per year and rising to just over MWK 1,500 million. Government or donors would incur around three-quarters of the cost, with the rest borne by mothers in terms of time and inconvenience.

The benefits of an increased rate of breastfeeding come in the form of averted child mortality, averted child morbidity, and averted stunting. An estimated 313 deaths are averted from the first year of the intervention. This rises to 409 averted deaths from the fifth year as the number of mothers targeted increases from 100,000 to 150,000. An estimated 82,000 cases of diarrhea and acute respiratory infections are also averted from the first year of the intervention, rising to 158,000 in the fifth year. Finally, 264 children avoid stunting from the first year of the intervention, rising to 396 children from the fifth year.

Almost all (93%) of these benefits would accrue to the children and their families, with 7% of the benefit to the health system in terms of avoided costs of treatment.

Figure 3: Total Costs and Benefits of BFP

Complementary feeding promotion (CFP)

This intervention targets mothers about to begin weaning their children and is largely intended for food-secure households that can respond to the promotion by providing adequate complementary food.

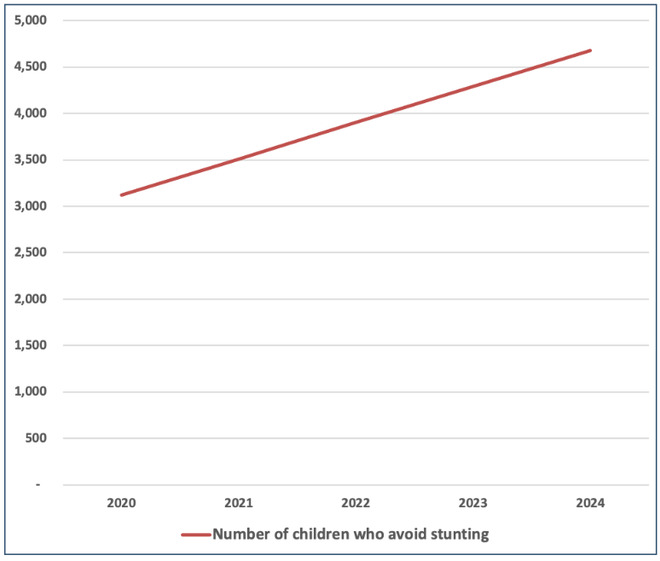

Figure 4: Impact of Complementary Feeding Promotion on Child Stunting

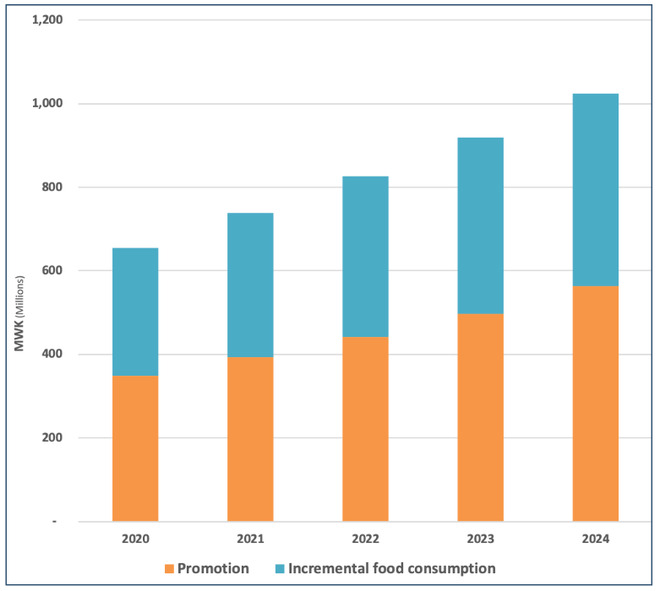

There are two components to the cost: the cost of promotion (53% of the total cost), incurred by the government; and the incremental cost of food (46% of the total cost) provided by the mothers to their children, which is paid for by the household. The total costs of the intervention are MWK 4,142 million, starting at just over MWK 600 million annually, and rising to just over MWK 1,000 million annually in the 5th year.

Figure 5: Total Cost of Complementary Feeding

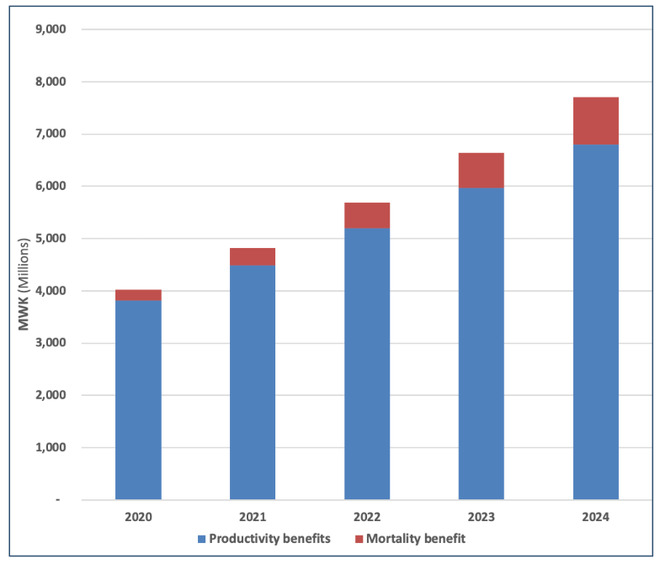

The two benefits are averted child mortality and 30% increased productivity via higher lifetime earnings of people who do not suffer stunting. The prevalence of stunting (in food-secure households only) is estimated to reduce by 7 percentage points (from 29% to 22%), while 3,100 children avoid stunting in the first year, rising to 4,679 in the fifth year. Most of the benefits are accrued due to productivity benefits from avoided lifetime income losses which account for nearly 90% of total benefits in this case.

Figure 6: Total Benefits of Complementary Feeding

Summary Table

| Intervention | BCR | Target Population | Cases of Stunting Averted | Cases of Death Averted | Cost per case of stunting averted | Cost per death averted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Feeding Promotion | 5.4 Good | 100,000 mothers in the first year, rising to 150,000 in the fifth and final year | 1,650 | 2,088 | MWK 3.7m | MWK 3m |

| Complementary Feeding Promotion | 7.2 Good | 100,000 mothers in the first year, rising to 150,000 in the fifth and final year | 19,495 | 331 | MWK 0.2m | MWK 12.5m |

Note: BCRs are based on costs and benefits discounted at 8% (see accompanying technical report). BCR ratings are determined on the following scale Excellent, BCR > 15; Good, BCR 5-15; Fair, BCR 1-5; Poor, BCR < 1. This traffic light scale was developed by an Eminent Panel including several Nobel Laureate economists for a previous Copenhagen Consensus project that assessed the Sustainable Development Goals.

Download the full policy brief here.