Can they change the country's future?

by Bjorn Lomborg

If you had Tk. 250 billion to use for Bangladesh's future, how would you choose to spend it? That would alter the spending of roughly just ten percent of what the national government and international aid agencies combined spend in the country each year.

It may sound like an infinite amount of money, but the more you spend, say, on education, the less you have to run hospitals, fight pollution, boost agricultural productivity or use on the multitude of other deserving areas. How do we know which issues we should tackle first, or where we should spend more or less?

Since early 2015, the Bangladesh Priorities project has commissioned teams of dozens of specialist economists from Bangladesh, South Asia, and around the world to study 75 concrete solutions to improve the future of the country. The idea is that education economists, to take one specialty, analyse the best education solutions for Bangladesh, estimating the costs and benefits of each, and showing how many takas of good one extra taka spent would achieve. In that way, the project, a partnership between Copenhagen Consensus Center and BRAC, can help everyone figure out the smartest ways to promote development and prosperity for all Bangladeshis.

From May 9, an eminent panel of four of economists have met in Dhaka to discuss the results. The panel includes Finn Kydland, Nobel Laureate economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Selima Ahmad, President and founder of the Bangladesh Women Chamber of Commerce and Industry, KAS Murshid, Director General of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, and Mushtaque Chowdhury, Vice Chair of BRAC.

Having read all the research, the panel spent the next three days discussing and challenging the findings with all the specialist economists. So, when the education economists had found that one of the best ways to improve education was to put children into different classes according to ability, the eminent panel would quiz the assumptions and probe the outcomes to see if this finding indeed stands up.

At the end, the panel's hard task was to answer where Bangladesh can best spend additional money—essentially, where the government and the development agencies should spend the next 250 billion taka.

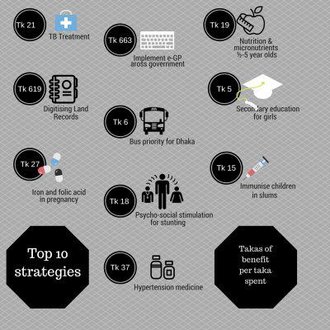

The panel handed over the full list of priorities on May 12, and the top ten are listed in this infographic.

The panel handed over the full list of priorities on May 12, and the top ten are listed in this infographic.

At top came treatment of tuberculosis, which kills about 80,000 Bangladeshis annually. Spending just Tk. 7,850 per patient on standard drugs and community clinic follow-up can avert TB transmission, leading to benefits 21 times higher than the costs. Missing benefits like avoiding families losing their breadwinner and communities losing their experienced workforce mean the real impact could be even higher. This is why the Eminent Panel ranked TB treatment first.

In second place came e-procurement - better spending of the Tk. 720 billion the government spends each year to pay for everything from Padma Bridge to pencils in government offices. Changing the procurement system from its current antiquated and inefficient one to a format similar to an online bidding system can increase competition and decrease corruption. The research estimates that this would reduce government costs by 12 percent. It is also relatively low-cost, implying low risk. Each taka of spending stands to do more than 600 takas of good.

Early nutritional interventions, which are vital in determining long-term outcomes, was ranked third. Nearly one-in-four children in Bangladesh under the age of five are considered “stunted,” which hinders mental development, lowers school performance, and leads to worse health outcomes and more disease later in life. The analysis indicated that benefits of nutrition-focused improvements are 19 times higher than the costs, which are low.

The panel ranked digitisation of land records fourth. Three different ministries currently oversee the records, and the laborious and time-intensive system is inefficient and costly. Instituting electronic records would make transfers much simpler and save huge amounts of time and money, but the largest benefit would come from increasing the security of property rights across the country, which are closely linked to higher economic growth. In total, digitisation would likely bring benefits in terms of economic growth of more than Tk. 160 billion over the next 15 years.

Other promising strategies from the top 10, included bus transportation investments in Dhaka, early-childhood education to overcome stunting, and immunising children in urban slums.

But when we say what should come first, we also need to say what should not come first. This is difficult and may even seem uncaring. But if we do not prioritise, it does not make prioritisation go away - it means we end up spreading resources thinly across great and poor policies alike, or simply allow opaque bureaucratic processes to do the prioritisation for us.

The panel pointed out that, for instance, cervical cancer should not come first. This is hard. It kills about 10,000 Bangladeshi women each year, but it is very costly to treat each woman. Compare that to the fact that more than twice as many women die from tuberculosis, which also kills many men and children. For the amount of spending that can save one person from cervical cancer, we can save nearly 50 from tuberculosis. Not saving these 50 people first is morally problematic.

Likewise, the panel also showed what does not work. Out of dozens of policies aimed at improving education, for instance, fewer than half showed any positive effects on child-learning outcomes—these included things like getting students more textbooks or using computers in the classroom. In other words, you are more likely to do nothing than to get it right when it comes to strategies aimed at improving schooling. Other alternatives that also ranked very poor were expensive polders built in places where they would likely not prevent flooding, unconditional cash transfers to fight poverty, and vocational training - each of these proposals returned less than one taka in benefits for each taka spent.

There are 160 million Bangladeshis, and there are probably 160 million different opinions about the best ways to help the country prosper. But without real evidence about what works, deciding between all the options is a little bit like being handed a menu at a restaurant that has mouth-watering descriptions listed beside every meal, but no information about the price you have to pay for each, or the amount of food that would actually come on the plate.

With the results from Bangladesh Priorities, we have put prices on the menu, and we can all see exactly how much we pay for each option, and exactly what we get in return. But this is only the beginning. We hope that we have kick-started the real conversation about Bangladesh's top priorities around dinner tables and within the political and administrative realm.

We will work with youths around the country to establish the priorities with tomorrow's leaders, and BRAC will collect priorities from the rural ultra-poor. Together with readers from The Daily Star, I look forward to continuing the conversation on the top priorities for Bangladesh. Now at least, we have the evidence to help make Bangladesh' future even better.

Dr. Bjorn Lomborg is president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, ranking the smartest solutions to the world’s biggest problems by cost-benefit. He was ranked one of the world’s 100 most influential people by Time Magazine.

This article was originally posted in The Daily Star.